As a former barber, and as an antique collector/dealer/appraiser/what-have-you, I have been a passionate collector of vintage hair and beauty products and advertising for many years. Here is a little overview of some of them:

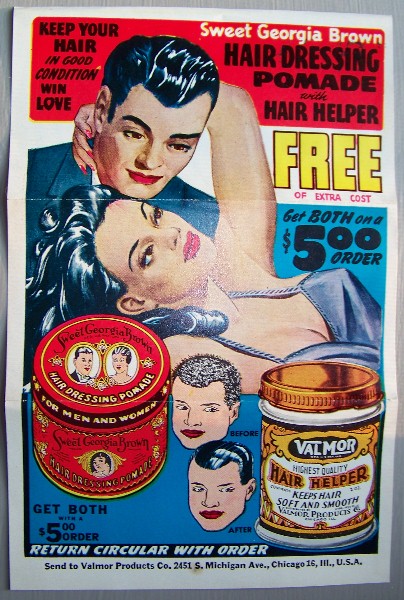

Valmor Products (Madam Jones, Famous Products, Sweet Georgia Brown, Lucky Brown, etc.)

African-American entrepreneurs created the ideal of Black Beauty in 20th century advertising. It was an important component to their success – and failure: black beauty quickly became a socio-political and economic issue.

As blacks moved out of slavery and into the workforce, ministers and activists worked hard to emphasize good hygiene and a clean appearance as a way for black people to win jobs from white employers. Black cosmetic companies wanted their ads to deliver the same message, but owners like Madame CJ Walker thought the idea would inadvertently result in blacks forgetting their heritage and trying to look like whites. Good grooming was one thing – bleaching creams and hair straighteners were another. Companies like Walker’s refused to sell them.

Black business leaders were extolling Race Pride but contradictions in the black psyche slowed progress: the New Negro hated being portrayed as Mammy, but the black standard of beauty was as old as Antebellum – alabaster skin, aquiline nose and thin lips. America still classified people by skin tone, and blacks were no different from the white norm. The world was changing, but beauty ideals remained very conservative -- and very European.

It was a fact that didn’t escape the attention of white entrepreneurs. They were eager to tap into black buying power, but they knew a good price wasn’t the only thing that influenced blacks to buy. After World War I, many white cosmetic companies started including “specialty lines” for black women. Start-up companies built up their businesses by manufacturing toiletries for African-Americans, undercutting black businesses with cheaper prices, spending more for ad revenue in black periodicals – and using language they knew had distinct meanings among people of color. Bleaching creams were called “skin brighteners” – offering the promise of clearer skin, perhaps lighter skin. Black businesses began to struggle to stay in the game.

But it was the Great Depression and sex that closed the door on black cosmetics companies and made Valmor Products one of the top cosmetic firms among black women. The issue of black beauty became de-politicized in black newspapers during the 1930’s and was replaced by anything that took people’s minds off hard times – articles on movie stars, romance and the psychological effects of beauty.

Valmor aggressively promoted the idea of romantic love with its products – not only would its skin brighteners and creams help deliver the man of your dreams, but perhaps marriage and a better life. According to author Juliann Sivulka, the advertising concept helped Valmor “successfully re-package Anglo-Saxon 19th century ideals and gender roles.” New mass media wasn’t just influencing white Americans, but African-Americans as well. Valmor came out on top, its dominance of the black cosmetics industry “signaled the end of an era (that) promoted beauty as a means of racial pride and “adjustment.”

It would take more than thirty years, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, the Nation of Islam and James Brown before Black became beautiful again. Eventually black-owned and operated companies such as Afro Sheen squeezed Valmor products out of the black beauty game forever.

On Morton Neumann:

On Wednesday, April 1985 Morton Neumann’s obituary in the Chicago Tribune newspaper read, “City’s Patron of Art Dies”. Only one line mentioned he was a ‘local cosmetics manufacturer’.

Neumann amassed one of the finest modern art collections in the world, and helped finance the expansion of Chicago’s Art Institute – all made possible because of the success of Valmor Products, its numerous subsidiaries – and the subconscious wishes of millions of African-Americans.

Before he started collecting Picassos and Giacomettis, Neumann tried his own hand at art. According to the book Stronger than Dirt, Neumann designed all of the labels for his Sweet Georgia Brown, Madam Jones and Lucky Brown Cosmetics lines. He used a process called Letterpressing – best described as a press made specifically for relief printing. You can tell it’s a relief print because the thick lettering’s raised a fraction of an inch above the label.

There’s no written explanation why Neumann decided to do all the artwork for Valmor Products himself – probably because it was too expensive during the 1920’s and ‘30’s to contract another company or artist to do something he could do himself.

It goes without saying Neumann’s designs have lived long after the demise of Valmor – and his own life. But for many, the empire he created will continue to live on in numerous discussions about art, the psychological complexity of advertising, and how capitalism benefited from racism.

An interesting note:

Morton Neumann didn't do all the artwork for Valmor....Charles C. Dawson did quite a bit of the artwork for the company http://planetbarberella.blogspot.com/2011/12/on-charles-c-dawson-graphic-designer.html It is said that Neumann never let Dawson sign any of the work he did for whatever reason. (I just had to add that note.....It seemed that Dawson was reduced to doing ad work for this company during the Depression, and he didn't even get credit for that. The story that (white) Neumann did the artwork apparently lives on, even today....)

Here's some Valmor advertising:

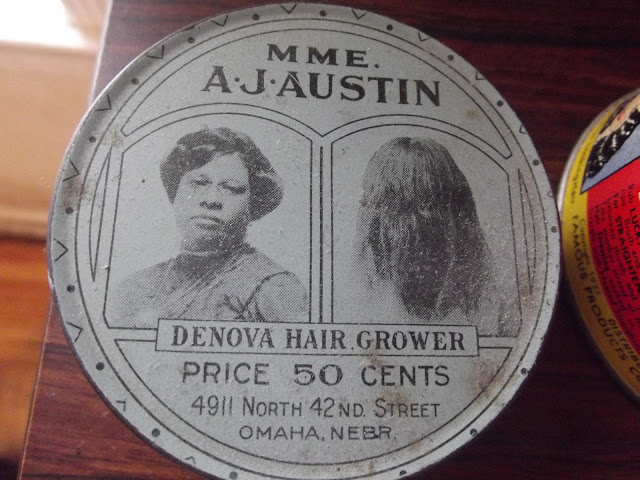

A few from my collection:

A few from other companies, including the black-owned Murray's:

Some King Novelty Co.(Valmor) items:

Amazing stuff.

ReplyDeleteI am sticking to my Coal Tar soap.

do you sell those pomades?

ReplyDelete"Bed Bug Murder." Nothing sells a product like putting the word MURDER in the title.

ReplyDeletekyrie 7

ReplyDeleteTravis Scott Jordan

golden goose outlet

Do U trade? im interested in the denova hair grower andn35 cent nu nile

ReplyDeletemy email kandy_hearts@yahoo.com

Delete